Acanthamoeba Keratitis and the Holiday Season

By Martin Conway

Acanthamoeba Keratitis is, thankfully, an extremely rare infection that, in the developed world, is predominantly found in contact lens wearers¹.

Symptoms include:

- Eye pain and sensitivity to light that may seem disproportionate to that of a “normal” eye infection

- Eye redness

- Blurred vision

- Sensation of something in the eye

- Excessive tearing

In the United Kingdom (UK), there are more cases each year than in the rest of Europe combined. That is not because the UK contact lens wearer is any less compliant than those in the rest of the world, but because here in the UK, even newly built homes have water storage tanks in the loft. In most countries, water is derived from the mains, however, in the UK, only water supplying the kitchen is normally fed directly from the mains. The rest of the house, including the bathroom, receives its water from a storage tank in the loft. These are normally covered, but they can still be home to an interesting variety of wildlife feeding from the sludge that collects in the bottom of the tank.

As contact lens wearers normally prefer to insert their lenses in the bathroom rather than over the kitchen sink, we can see that the risk of contamination of lenses and cases would be therefore much higher in the UK than in the rest of Europe.

The reason I thought that it might be useful to remind ourselves of the risks associated with using tap water and contact lenses, is that we are now coming into the holiday season. Many wearers, even those from countries with less archaic public water systems than here in the UK, may be travelling to the UK or even less developed countries for their much-awaited break in the sun.

I thought now would be a good time to re-acquaint ourselves with Acanthamoeba and its risk to the unwary.

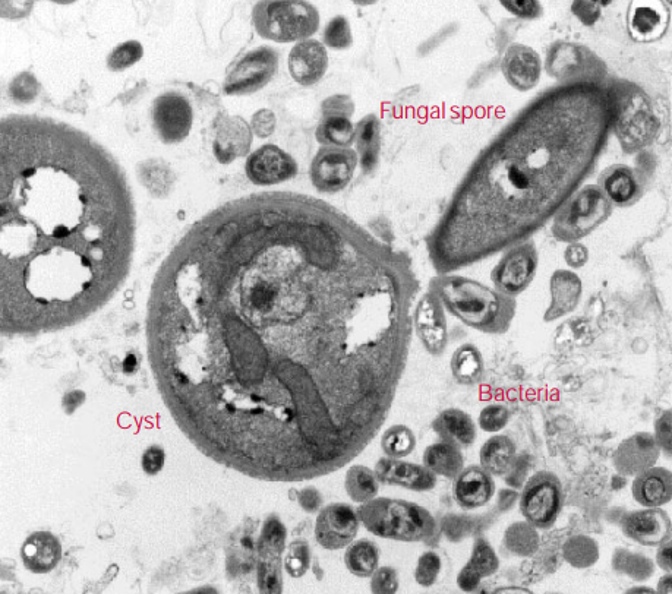

Acanthamoeba Trophozoite

The Acanthamoeba trophozoite is present in most aquatic sites around the world and is different to most of the pathogens normally associated with contact lens related keratitis in that it resists most commonly-used disinfection systems. Its survival is linked to its ability to transform into a cyst form when in a hostile environment, or when its food source is unavailable. In the cyst form, it is resistant to many forms of antibiotic and chemical treatments and can also survive desiccation and starvation. It then emerges from this protective shell in order to continue feeding and replicating. It has been found in treated swimming pools and most other water supplies including both tap and bottled water.

Numerous microbes can cause eye infections, and contact lens solutions are effective against the most common, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, several yeasts and fungi (Candida albicans, Fusarium and Aspergillus). However very few will completely eliminate Acanthamoeba in its cyst form.

Acanthamoeba and Contact Lenses

The contact lens wearer is much more susceptible to Acanthamoeba because of the potential for the surface of the cornea to be disrupted by normal insertion and removal. If they then introduce the trophozoite from their case, or the hotel shower or tap water in the case, then the risk escalates.

If Acanthamoeba is present in the case, then the addition of a Multi-Purpose Solution alone will not eliminate it. However, it will eliminate its food source and hopefully, it will therefore remain inactive in the cyst form.

Peroxide will kill both the trophozoite and cyst forms, but only if the full 3% peroxide is in contact with the cyst for 4 hours. Unfortunately, most peroxide-based systems these days are one-step systems which neutralise the peroxide long before this time has elapsed – leaving the cysts intact and ready to emerge once a food source is present. Two-step peroxide systems when the lens is stored overnight in peroxide are effective but rarely used these days.

Eliminating Acanthamoeba

There is good news, however! Acanthamoeba in both cyst and trophozoite form can be effectively removed from the surface of a lens with simple rubbing with a surfactant. During their investigations into Acanthamoeba, research led by Dr Simon Kilvington of Leicester University, UK, found that they had difficulty keeping the trophozoites on the surface of soft lenses whilst using a conventional stirrer. It was only when it was turned down to its lowest setting that they could keep them on the surface during testing! This is because they are a single-cell creature, much larger than a bacterium. The trophozoite is 15-45 microns in length and the cyst is 8-24 microns in diameter. Bearing in mind that the epithelium itself is only 50 microns deep and can be easily resolved by OCT, the simple step of rubbing and rinsing, if done properly, should eliminate both forms of Acanthamoeba together with most other microbial contaminants. The need for the elimination of tap water from contact with lenses and cases should be repeated at every possible contact with patients, and in particular at holiday times when normal routines are likely to be disturbed or compromised.

As we emerge from COVID lock-downs and head for the sun, it is important to stress to wearers that the water that emerges from taps in their hotels is not necessarily of the same quality as that at home. Just as they prefer to use bottled water when cleaning their teeth, it is important that the correct disinfecting and storage solutions are used for their lenses.

If you wish to know more about Acanthamoeba Keratitis then I recommend the following:

- Through a glass darkly – Contact lenses and personal hygiene by Simon Kilvington, Microbiology Today (https://socgenmicrobiol.org.uk/pubs/micro_today/pdf/050003.pdf)

- Acanthamoeba Keratitis: The Emerging Vision-Threatening Corneal Disease by Lidia Chomicz, Jacek P. Szaflik, Marcin Padzik and Justyna Izdebska (https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/51734)

1.J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2015 Jan; 62(1): 3–11. Published online 2014 Sep 25. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12149

Martin Conway has over 40 years’ experience in the contact lens field as a qualified Contact Lens Optician. He is registered with the UK General Optical Council on the Speciality Contact Lens Register. Martin is a fellow of the British Contact Lens Association (FBCLA), and The International Association of Contact Lens Educators (FIACLE). He has served in the Professional Services role as an educator and clinical adviser on behalf of both Sauflon and CIBA, and now acts as Professional Services Consultant for Contamac. Martin has lectured extensively in Europe, Asia, Russia, North and South America and the Middle East.